In one of the recent Coderetreats, we did an Outside-In TDD session. I paired with a guy who was new to this, and I noticed a challenge in expressing my ideas well. Honestly, I don’t think I did a good job, so I decided to write about this topic.

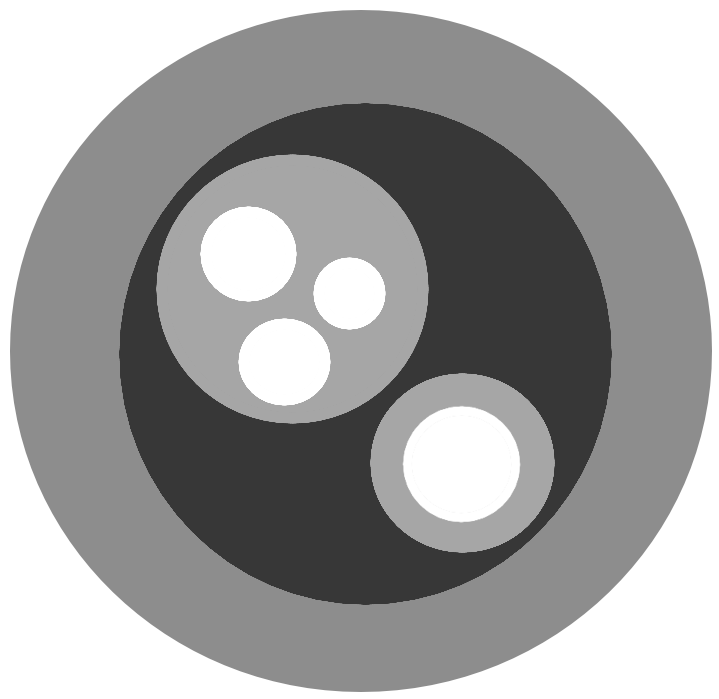

A Software System

Suppose we’re developing a thing, a program.

It will inevitably become a hierarchical system composed of collaborators that form the sub- and sub-sub systems. Each of those will solve yet another problem, and together they will form our thing. The outer layers will be more concerned with infrastructure and coordination, whereas the inner parts will be concerned with the business logic, the domain.

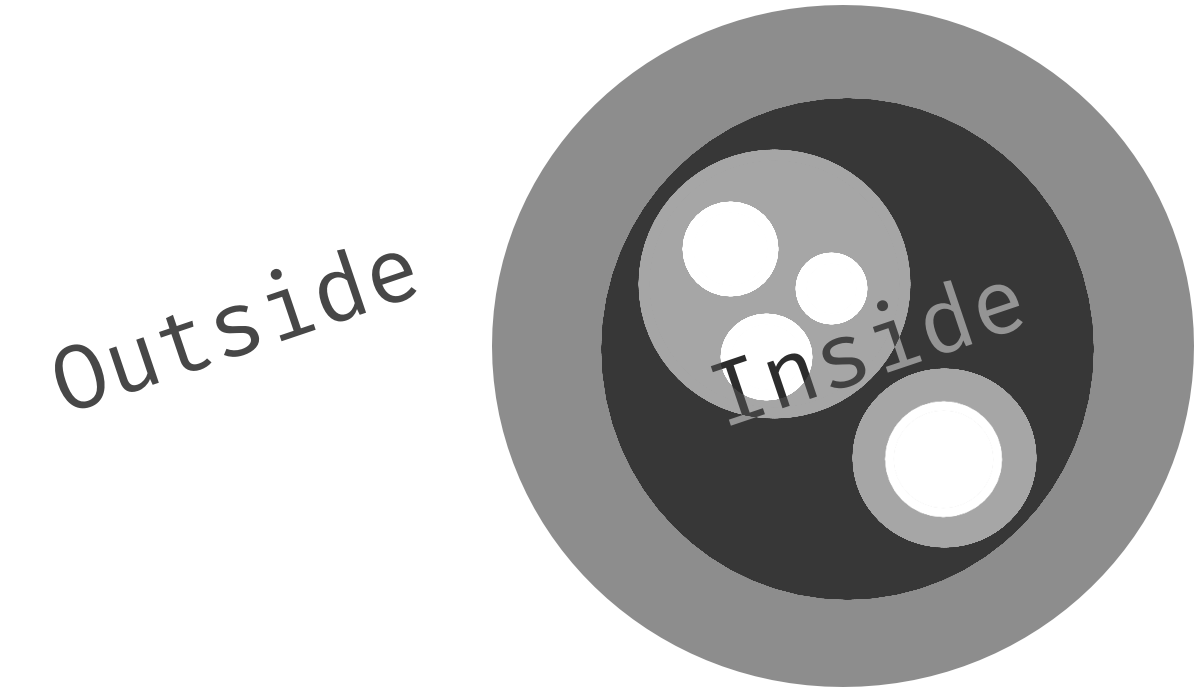

Outside vs Inside

When we design the thing we can start on either side, the outside or the inside.

The Outside

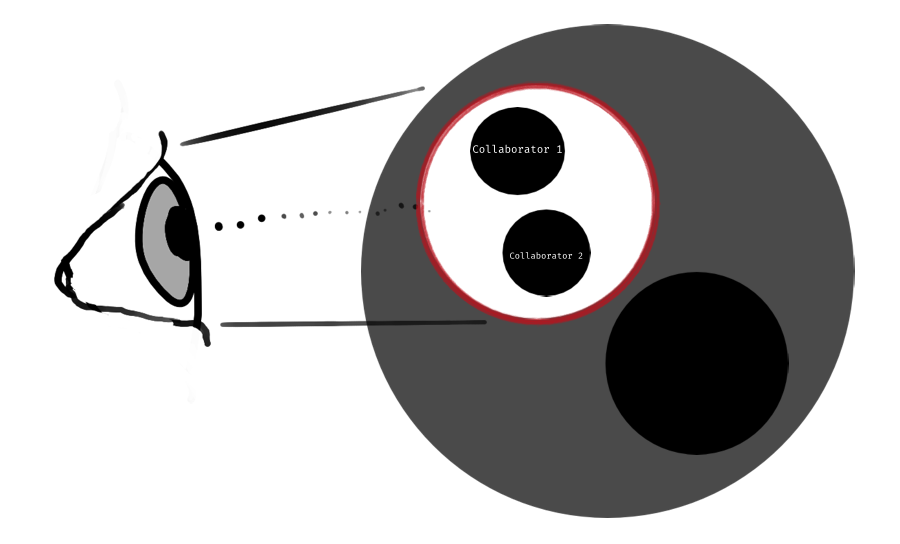

The outside is where the users of the thing are. Users might not just be humans, but also other software systems. They observe the thing from the outside, and they cannot see inside of it. But they don’t even care about its inside. All they’re interested in is what it does, and how to interact with it.

So to them, it is a black box.

The Inside

The inside contains the hidden details of the thing - its gear, its structure. It represents all the subproblems the thing was broken into. The inside answers the question, how the thing accomplishes what it was designed for.

Inside-Out Design

In Inside-Out Design we start at the inside and gradually ascend outwards. So we first break the problem down into smaller subproblems and define how they interact with each other. In doing so we identify the most inner pieces, the domain of the system. Doing Inside-Out, they are exactly where we want to start. After all, they will be the foundation for the remainder of the system. They are the collaborators we use as soon as we ascend to build the next higher layer. As we ascend further and further outside we will at one point arrive at the outermost layers. They form the interface of our system, the entry point users may interact with. As we build those last, they will be guided by the structure and behavior of the subsystems that have already been built. So they will be biased towards the early decisions we made when we first designed the domain. I think that a good example of an API that is biased towards its domain is the CLI of git. You see that in the sophisticated helper tools, scripts and aliases that attempt to make it more accessible.

ⓘ Inside-Out is domain-centric. Can cause the Interface to be biased towards early domain decisions.

Stereotypes:

We cannot know what the domain will look like in advance, it is shaped by how users will want to use the system.

A bias towards the domain makes the interface more complicated.

To preserve a sound Interface, we might have to make ugly adjustments in the layers above the domain.

Thinking about usage last will cause us to build features nobody will ever use. (YAGNI1)

Outside-In Design

When we start from the outside we don’t care about the domain at first. Instead, we focus on the users and how they would want to use the thing. So we imagine the thing as a black box while defining its interface as simple and practical as possible. It will be doing what it should do, but we will care about that later.

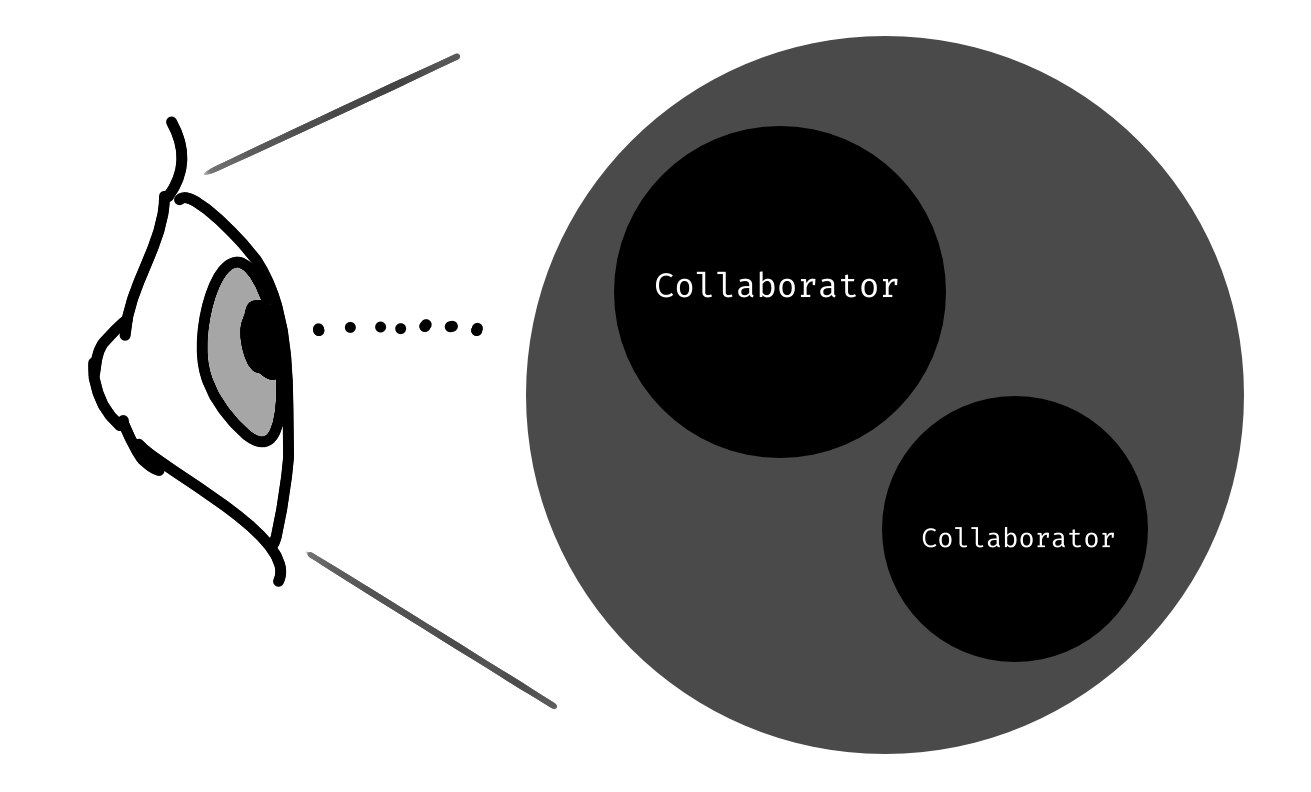

Once the interface is defined we descend inwards, thinking about how we can bring this entry point to life. Now we have to decide what collaborators will be needed, and what their responsibilities will be. So from this perspective, the entry point we just defined is now the new user. Again, we’re treating its collaborators as black boxes. And again, at first, we only care about what they do, but not how.

We descend further until we arrive at the core, the domain.

As a result, the built system will be biased towards the anticipated usage of the thing.

ⓘ Outside-In is user-centric. The implemented solution might be biased towards the anticipated usage.

Stereotypes:

- We’re bad at predicting how users will want to use the system.

- A bias towards usage makes the domain unnecessarily complicated.

- Thinking about usage first will help us avoid building stuff we don’t need. (YAGNI1)

Descending in Outside-In TDD

When we test drive the thing Outside-In, we may start with an acceptance test as in double loop TDD. It describes the thing and its interface in a simple example: How it is used, and what it does. Of course, the test does not work, as there is no thing yet. We can now keep the test red until it passes, or we just disable it. But our goal is to make it pass. So we write another - this time a unit test, to guide us towards writing the code that will make the acceptance test pass.

And this is already the first of three descending strategies which I call: “Skip and Descend”. The other two are “Fake it till you make it”, and “Replace with Test Double”. But when we build a full slice from the entry point all the way down to the domain, we mostly don’t use just one strategy, but a combination of these. Every time we descend we have to make another judgment call about which strategy fits best this time.

Skip and Descend

In Skip and Descend we use a test to drive the decision which immediate collaborators will be needed to suffice the test. But we acknowledge the fact that implementing those collaborators on the basis of this test would be too big of a step. So we disable the test and descend to start test driving the just defined collaborator. Sometimes we may rinse and repeat until we arrive at a leaf whose unit is small enough to be implemented. After implementing the leaf we would ascend again to the previously disabled test where we would then use the collaborator we just built. Kind of like mikado.

Leads to sociable unit tests and test overlap2. Where test overlap happens we aim to minimize it and use the sociable unit tests to cover integrations only.

Use when

- Confident in the need of the collaborator.

- The sociable unit test will be fast:

- The collaborator is doing in-memory instructions that finish within milliseconds.

- The collaborator is going to be a fake that will be replaced by a real system later.

- The collaborator is inside the application boundary.

- The collaborator is not interacting with an expensive system such as a database or a web service.

- The call to the collaborator is not a notification3.

Advantages

- Avoids test doubles4, and as such decouples the tests from their implementation to enable refactoring5.

Disadvantages

- Need to manage disabled tests.

- Can lead to premature collaborators.

Fake it till you make it

In fake it till you make it we don’t necessarily decide on a collaborator and descend. Instead, we write the simplest and stupidest expression that will make the current test pass. We then write more tests to force us to change the stupid and specific expression into something more generic. We might have to apply preparatory refactorings in the process. With those, we place seeds as we extract new collaborators that grow while we write and pass more tests. May also lead to sociable unit tests and test overlap.

Use when

- Unsure which collaborators to create at first.

- The SUT (System Under Test) remains inside the application boundary.

- The SUT is not interacting with an expensive system such as a database or a web service.

- The call to the collaborator is not a notification.

Advantages

- Avoids test doubles4, and as such decouples the tests from their implementation to enable refactoring5.

- Collaborators emerge out of triangulation and are therefore more mature.

Disadvantages

- Testing subcollaborators from a distance.

Replace with Test Double4

When we are confident in the need of a collaborator, we may decide on replacing it with a test double. This allows us to finish the implementation of the current SUT before having to descend.

Use when

- Confident in the need of the collaborator.

- The collaborator is at the application boundary.

- The collaborator is at the boundary of the module.

- The collaborator interacts with an expensive subsystem such as a database or a web service.

- The call to the collaborator is a notification; we like to use a mock in this case.

Advantages

- Avoids test-overlap.

- Can finish the SUT before having to descend.

- Allows simulating expensive subsystems such as databases and web services.

Disadvantages

- Couples the structure of the test to the structure of the implementation.

- Mocks typically less performant than hand-written test doubles.

- Hand-written test doubles are an additional effort to write.

Conclusion

Mocks are not the only way to descend in Outside-In TDD. There are many strategies, each of which has different trade-offs. So we have to make a judgment call every time. We need to keep an eye on refactorability when writing our tests. Sociable unit tests can improve refactorability, but we have to keep the test-overlap low. So we avoid testing all the details from a distance.

-

Test overlap is when more than one unit tests cover the same thing thus may fail for the same reason. ↩

-

A Notification a.k.a ‘fire and forget’ is a type of relationship between objects where one object just notifies another. I first read the Term in the GOOS Book. To test notifications we prefer to use mocks or spies. ↩

-

A test touble replaces a real collaborator in a unit test, just as a stunt double replaces the real actor in a scene ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

Tests should be structure insensitive to enable refactoring. ↩ ↩2