I was recently following an interesting discussion of the Vienna software crafts community with the title: “How to facilitate a conversation between people, where the byproduct is code?”. The discussion is in German and contains interesting ideas about how to code well together, and how to facilitate it. I tried to give an answer, which got longer and longer. In the end, I chose to write this blog post which expands upon the original topic of discussion and covers a broader range of related subjects.

I will continue to use the terms

- coding together

- collaborative coding

- Mob Programming, and

- Ensemble Programming

interchangeably. However, when I say coding together or collaborative coding this includes Pair Programming. When I say Mob Programming or Ensemble Programming I exclude Pair Programming. By the way: Yes, Mob Programming and Ensemble Programming mean the same thing and may be used interchangeably. It’s just that the word “Mob” might be associated with something negative, whereas “Ensemble” is a more innocent term. However, I like to use “Mob” as a verb because it’s so short and simple:

- “Let’s mob on this problem!”

- “We have been mobbing on this problem.”

Solo Programming Considered Harmful

» A programmer is a person sitting solo in front of their computer, typing rapidly on their keyboard.

A well known stereotype. You have seen the movies.

» A programmer is a person sitting solo in front of their computer, typing rapidly on their keyboard.

A well known stereotype. You have seen the movies.

It turns out that solo programming may not be as good as we think. No, I’m serious. I think we overestimate our programming skills. We tend to overcomplicate things, and we make a lot of mistakes. We rarely understand the problem that needs to be solved, and we don’t know our tools well. We often end up with crufty code that isn’t as simple as it could be. It doesn’t work and often targets the wrong problem.

But hey, don’t worry about it. We don’t mean to. We try hard to live up to expectations. And we work to the best of our ability. We’re learning. It’s just not that easy. 🤷♂️

Coding Together as an Answer

Collaborative coding can greatly improve the situation. By bringing together multiple people with different skills and perspectives, we can gain a deeper understanding of the problem and develop a better solution. We can take on different roles and complement each other. We have more eyes to spot mistakes, and together we know our tools better and know more about valuable techniques and practices. It’s proven that complex problems can be solved better and faster through collaborative coding. Working on simple applications, we encounter such hard-to-solve problems every day. But the best thing about coding together is the amplified learning while having a good time.

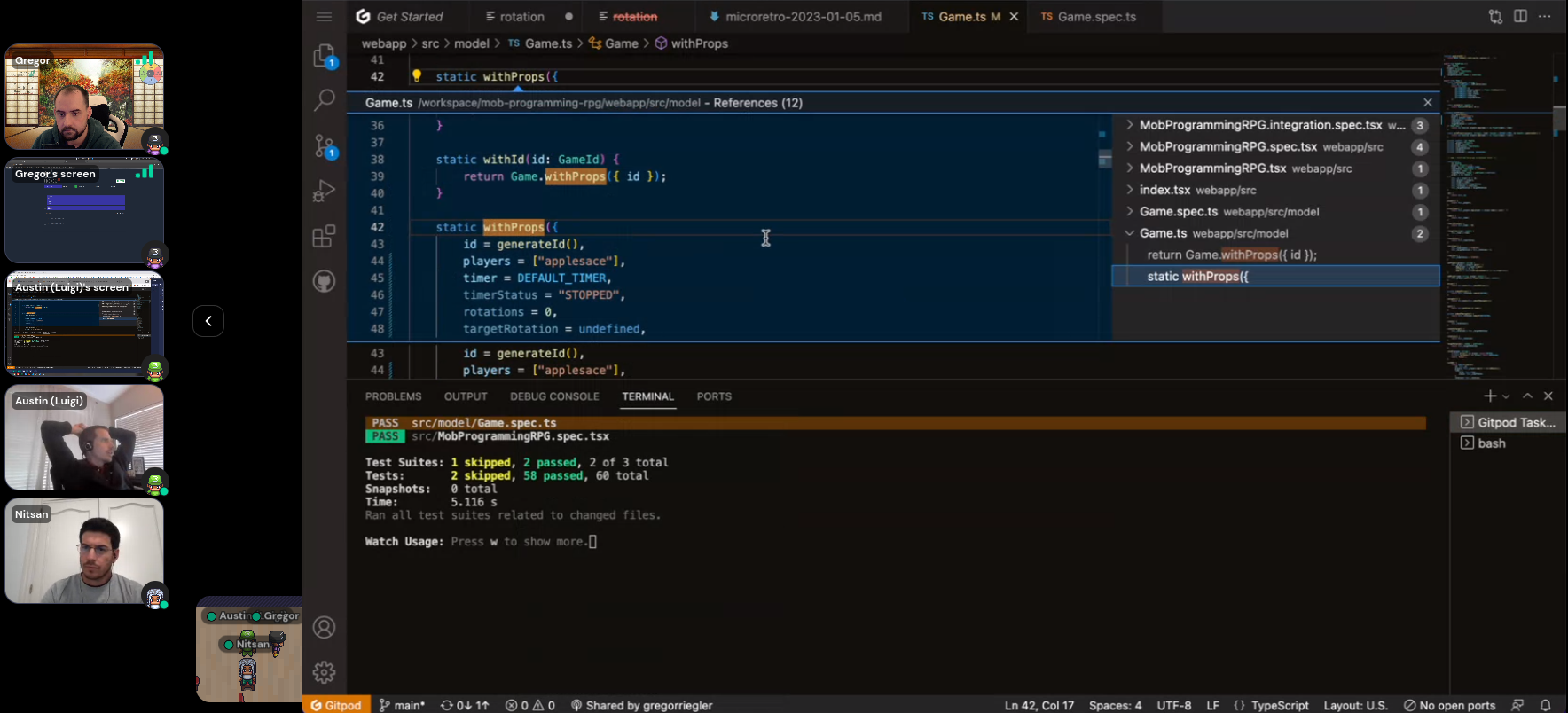

» A team coding together remotely.

» A team coding together remotely.

The Cost of Coding Together

There is a cost, of course, to having many programmers working on the same problem at the same time. We understand those costs well, I think. What we do not understand so well, however, are the benefits. Ultimately, it’s a tradeoff. Will the benefits outweigh the costs? So let us talk about the benefits.

The Benefits of Coding Together

Amplified Learning

The most striking advantage, and I cannot emphasise this enough, is the amplification in learning. We need to learn and get better at what we do, desperately so. All of us, but especially those of us who are new to it. There’s a big gap between what you learn in school and what you need to know on the job. We have to make up for that gap somehow. The thing that works best in my experience is to work together with the people. Coding together isn’t only the best way to onboard new people, but it also succeeds amazingly quickly in raising the level of participants and turning them into valuable contributors. I’ve learned so much myself through programming with other people that I honestly believe the learning effect alone makes up for the cost.

Reduction in Cost for Change

We are used to a trade-off between quality and cost, but it does not work that way with software. In our business, quality is cheap and cruft is expensive.

💡 Martin Fowler wrote an interesting article on this topic.

Code is a liability, and much of the cost is incurred when we need to change and improve it, which happens from day one. There is this strange idea that maintenance is something that happens after the project is completed. Well, that’s not exactly true. We maintain the code starting with the first day. It’s a challenge to find the right structure and keep it soft enough to change easily. It’s also terribly expensive to work on poorly designed legacy code, as we often see in enterprise software today. The cost of this is insidious because there is usually no awareness of it. So we should strive for and achieve high internal quality to save maintenance cost. The internal quality of the code can be greatly increased if many people review and revise the code as it’s written.

Better Software for the User

I have seen this repeatedly: Many minds working on the same problem produce more and better ideas, which simply leads to better solutions. When I say better, I usually mean simpler. It’s those moments when the majority chase a suboptimal solution and then one person proposes a better one. We need to think outside the box. Different people think in different boxes. More boxes mean more opportunities. More opportunities lead to a better outcome for the user.

Reduced Work in Progress

We know that high work in progress causes slow down. When we work together on one problem, it’s also the only problem we work on. All the people needed to solve the problem are there when they’re needed. And then, once we’ve taken all the necessary action, it’s done. It’s off the table. We can focus entirely on the next problem. No juggling of tasks. No waiting around. No context switching. Fewer things to keep everyone busy. Better and easier focus. A clean one-piece flow.

Having a Good Time

For many people, it can be rewarding to work in a mob with other people, especially if they’re more experienced. When working on software, we’re often thrown in at the deep end. Teamwork reduces the stress involved in this. It’s also more enjoyable for many. Coding together is a great team-building activity because we work as an actual team. It may feel awkward at first, but once you get the hang of it, it can be a lot of fun.

Mob Programming is Not Easy

Coding together is challenging. It’s not simply a matter of one person typing while others observe in silence. In order to make it work, it’s important for all team members to actively engage and collaborate. This enables us to utilize all of our minds and build the shared understanding we strive for. Also, we want to reach a flow state and make continuous progress. Mob Programming, thus working as an actual team, is a deliberate practice.

Shared Understanding

It’s important to ensure that everyone is on the same page and no one is left behind. This requires patience, effective communication, and a willingness to listen and explain ideas. Communication is a challenge, but a skill we can improve with practice. Speak slowly and use simple language. Use metaphors and pick people up where they are. When starting out with a new ensemble, it’s common to feel slow at first. This is normal as the ensemble gets to know each other and establishes a shared understanding. After some time you should experience a boost in productivity. The duration of this initial phase can vary, it could be as short as a few minutes or as long as an hour.

So, it’s all About Human Interaction

Treat each other with kindness, consideration and respect1. Make people feel safe to contribute, and welcome all forms of contribution, including questions. Reward a contribution, especially if it makes the person feel unsure. It is perfectly fine not to know something or not to “get it”. Be a hero and ask the first question to make others feel confident as well. Be open to examining and evaluating potentially disruptive ideas, even if they come up suddenly. Creating a supportive environment that encourages people to contribute will help ensure that the best ideas and insights from all team members are incorporated into the code. It seems like social skills are the name of the game. Has programming been the easy part all along?

Agree on a Shared Goal

With many different ideas being shared, it can be difficult for a team to agree on a common goal. This is another team skill to master. It’s important to be open to taking a step back and trying someone else’s idea. It’s okay to try multiple approaches and see which one works best. By being open to different ideas and perspectives, a team can learn and grow together.

Knowing when to Speak

It’s important for everyone to feel comfortable speaking their mind and sharing their ideas. However, it’s also important to know when to hold back and listen to others. One way to deal with this is to keep a private backlog of ideas that come to mind but may not be relevant at the moment. This can help keep you focused on the task at hand while recording and considering other ideas for later. Knowing when to speak up and when to hold back is an important skill for effective collaboration.

Bias to Action

In a group, it’s sometimes easy to get stuck in a discussion that goes on forever without trying anything. Most of the time, it’s less stressful to just try. Some discussions just are not worth it. If you notice people talking for several minutes without writing any code, alarm bells should be ringing. For example, if people are puzzling over the behavior of a particular code for an extended period of time. It’s time to call to action and suggest that you simply run the code and see.

Distributing Roles

A logical first step is to distribute participants by what they do. Someone has to type the code, of course. A common name for this role is Driver, as in the Driver/Navigator relationship of Strong Style Pairing. I often find that people confuse the names of these two roles, so I prefer to call them “Typist” and “Talker” instead. May also use “Typing” and “Talking”.

The Role of the Typist

We do not want the Typist to just hack away. If they did, other participants could merely descipher the then buggy code and make incorrect assumptions. That’s not sustainable. We want the Typist to follow the team’s instructions instead. Being a Typist is hard. They may get overwhelmed with conflicting ideas. What should they focus on? We can solve this problem by using a designated Talker. It’s not the only person who speaks, but they act as the primary input channel for the Typist, filtering all the ideas and making the final decision. Even if many things are said, the Typist then knows which voice to focus on.

A Typist Translates

It is a common misconception that the Typist foolishly types out the code they’ve been told to type, word by word, character by character. Actually, the Typist must make many considerations and decisions. For example: They may choose to run the tests whenever. They translate the Talker’s intention into code so that the Talker can stay at the level of their thinking. The Typist takes care of the details. That takes a big burden off the Talker. I mean, typing in itself is quite a challenge. To know your tools well and being good at typing is an art. If you are then able to translate the high level intent on top of that, that’s icing on the cake.

Typist Wrapups

One technique I learned at the Python Approvals Mob that improves feedback and shared understanding is Typist wrapups. It means that a Typist gives a brief explanation of what just happened and what they did after each round. When a Typist explains this in their own words, misunderstandings are more likely to be uncovered and cleared up.

Being a Talker is not Easy Either

So the Talker is the person who programmes. The Typist acts as a kind of intelligent input device for them. A Talker should communicate their thinking. In other words, they should think out loud. There are many stages of thinking that we go through. First, we orient ourselves to the current situation - the context. Second, we imagine where we want to go from here - a direction. Third, we formulate a concrete intention - still at a high level. This is already what a Typist could work with. Each thought step is shared with the team. Only then, if needed, do we move on to low-level details: What code to write on what line, syntax, code formatting, keys to use, buttons to click, etc. The Talker instructs the Typist at the level at which they can operate on, the higher, the better. Kind of like inverted limbo: How high can you get?

Contributing while not Talking nor Typing

Not being any of those roles doesn’t mean you’re not contributing. You may step out of the mob for a minute, but what you rather want is to be creative in supporting the group. Do some research when an opportunity arises. Ask, if you don’t understand something. Remind people about the protocol if necessary. Think ahead and take notes about things we should take care of. Review the code as it is being typed. Observe how the group behaves and what they are doing. Maybe you have an Idea of something the group should be trying that could work well, bring that up. Note down things that worked well so you can bring it up in the retro.

Rotation

Everyone should get to type and talk. This keeps everybody engaged. When deciding on the rotation interval, consider how long it would take for the same person to become a Typist again. Waiting an hour to go back to typing is probably too much. It’s hard to maintain attention that long. A rotation every 2 or 3 minutes works very well with an experienced mob, but you need to be able to do it swiftly. Work hard to shorten your rotation time. Rotation time is the time between the start of a rotation and the next Typist/Talker being able to continue. The perfect rotation time is 0.

Rotations Need Trust

Ending your turn thus giving up control can be difficult. As a Talker, you not only want to maintain the direction of the previous Talker, but you must trust the next Talker to do the same. Trust them to continue the idea you have been working on. Without trust, rotations get bogged down, which hinders the flow.

Hard Rotations vs “Finish Your Thought”

When the timer sounds, you have the option to do a hard rotation, where work stops immediately and team members rotate positions. Another option is to take some time and finish your current thought, known as “Finish Your Thought” (FYT). FYT is useful for completing something small or finishing a line of code. However, when it takes too long, it can disrupt the flow of the team. People might forget or even ignore that the timer rang at all. Based on my experience, in those cases, it’s better to do a hard rotation. Trust in the next person to pick up where you left off and continue the team’s intent.

Calling out your Role

Another common practice that helps maintain flow is when everybody calls out their role when the rotation starts. It’s practical to also have the person that will be participating in the following rotation to call that out as being “next”. This avoids misunderstandings and it makes sure that the “next” person is increasing their attention towards being able and continue the given work.

An example would be:

Alice: “I’m Alice, and I’m talking!”

Peter: “I’m Peter, and I’m typing!”

Sarah: “I’m Sarah, and I’m next!”

Find out what Works for Your Mob

As mentioned earlier, Mob Programming is a deliberate practice. You want to constantly improve the way you work together. There are no pre-existing rules or frameworks for this. You need to find your own working agreements. Regular retrospectives are key in this regard. Conduct them at least daily. A two-hour Mob Programming session can lead to a three-hour retrospective, which is great. The learning effect can be tremendous. But they don’t have to be that long. Make them short, maybe a few minutes, but regular. Use them to find out what worked well for you, and put that in the spotlight. Turn up the good. Stay innovative and figure out what you’d like to try. Retrospectives are about learning and about change. Use it, act on its results.

Facilitating a Mob Programming

Above all, remind the participants to be patient and treat each other with kindness, consideration, and respect1. Be a role model in the way you treat them. People new to Mob Programming will be overwhelmed just by the conviviality of this way of working. Suddenly they have to pitch their ideas to other people. They are also not used to being exposed while typing code. It will take some time for them to get used to this way of working and still have some room in their head to keep a protocol intact. So you want the initial protocol to be minimalist, and you want to guide it. Too many rules would throw them off the rails.

Tip: When you notice someone being distracted, offer a short break.

Guide your Protocol

There is a fine line between telling everyone what to do all the time and letting them off the hook. In the beginning, they won’t remember how to follow your protocol. It’s just too much. So you should guide them and kindly tell them what to do and when. But you also don’t want to fall into the trap of doing everything for them. Your goal is for the team to be able to take care of themselves and for you to become redundant. Therefore, every time before you remind them, you should also give them some time to follow the protocol themselves. Once you become redundant, you may consider joining the mob.

Tip: Do not join a fresh ensemble as a facilitator unless you are very experienced in this. Facilitation can be complicated, therefor you do not want to particiate in the programming at first. Stay out of the ensemble and focus on having them work well together.

Keep Time for a Retrospective

You want to end a Mob Programming session with a retro. Give them the chance to express their feelings about what happened, and share it with each other. They probably enjoyed it. Also, they have probably learned new things in the progress.

Microretro

A minimal but nice format for a retro is a microretro. It only takes a few minutes and you could do it at least once a day. In this retro, ask these questions:

- How did that feel?

-

What worked well?

The aim of this question is to highlight the positive aspects and achievements. We want to celebrate what went well and strive to replicate it in the future. It’s easy to get caught up in dwelling on negative aspects, but this can lead to a negative mindset and impact the overall well-being of the team. Therefore, this retro focuses on shifting the perspective entirely towards the positive.

-

Do you have an idea you would like to try?

The goal of this question is to foster experimentation and innovation.

Tools for Mob Programming

- mob.sh is a commandline tool and git wrapper to easily hand over code in a remote mob programming.

- mobti.me is an online mob timer, and the best that I know.

- gitpod is a webapp that is basically vscode in the browser that works well for collaboration as you can share your workspace with others.

- remdev on azure is a script to easily boot up a virtual machine on azure for remote mob programming.

- cyber-dojo is a brilliant webapp to practice mob programming on a kata. All you need is a browser.

- tmate allows you to share your terminal with others to collaborate.

Public Mobs

If you want to try Mob Programming you may choose an existing community.

- MobRPG Mob is a weekly public remote mob on thursdays where we develop a webapp for the mob programming rpg. Read the Contribute section to find out how to join (It’s dead simple as in “just show up”).

- Code Crafts Saturdays and Sundays is a monthly event where you can try and practice Mob Programming and TDD.

- Python Approvals Mob is a weekly remote mob that works on the python version of the approvals testing library.

- Mobus Operandi has a calendar with a lot of public mobs that you can join.

Further Links

- Mob Mentality Show

- Mobbing Discussion (I particularly like this episode because Tim explains very well and shares valuable insights)

- Resource Collection on Mob Programming and Software Profession

- Mobbing Pattern Language

- Scatter Gather (The hidden cost of Solo Programming)

-

Kindness, Consideration and Respect are what make a healthy Mob Programming. ↩ ↩2